A Jewish–Arab Party Is a Challenge to the Existing Order

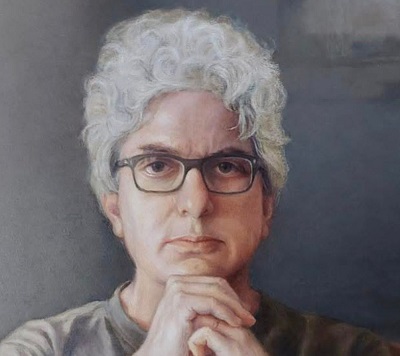

- Dr. Bashir Karkabi

- 16 hours ago

- 4 min read

By Dr. Bashir Karkabi

On Friday, January 23, 2026, an advertisement was published in Haaretz calling for the establishment of a Jewish–Arab party. Hundreds of Jews and Arabs signed the ad, including the writer of these lines. Within hours of its publication, criticism of the ad’s content began to be heard, some of it angry. Before addressing these criticisms, I will try to present the rationale underlying this initiative.

The Joint List Can Lead a Proper Educational Vision in Israel

I was born and raised in a communist home, and from there absorbed much of my worldview. Throughout most of my adult life, my political activity took place within the framework of Hadash (The Democratic Front for Peace and Equality). Toward this party, and especially toward many of its active members, I feel affection and camaraderie.

However, over the years I encountered the limitations of this party, particularly regarding its activity among the Jewish public. Since the split in the Communist Party in 1965, and throughout all election campaigns, Hadash has not succeeded in recruiting more than a few thousand Jewish voters. As early as 1977, the Communist Party itself recognized this limitation and initiated the formation of Hadash together with the “Black Panthers” and independent figures.

This attempt to broaden Hadash’s activity was not crowned with success, but the understanding that a political initiative beyond the existing frameworks was needed remained intact. With the establishment of Balad (National Democratic Assembly), competition emerged between Hadash and Balad over the Arab vote. Naturally, this competition gradually changed Hadash’s practice: its discourse, vocabulary, and mode of addressing audiences — even if not its core principles.

There are additional problems in the parties representing the Arab public. The traditional structure, particularly its male dominance, alongside the small number of young people in leadership positions, distances large segments of Arab society. We must ask: why do only 40% of women and only 25% of young people aged 18 to 24 in Arab society vote? Therefore, we must ask how we can convey an inspiring message of hope that will lead the Arab public to the ballot boxes in large numbers, and what kind of political imagination can enable this.

Some operate in the political arena to express anger and protest, while others seek to organize the Arab public in a struggle for its rights against an establishment that is becoming increasingly violent and racist. All these goals are legitimate and worthy. We, the signatories of the ad, aspire to bring about change in Israeli society: to replace the idea of Jewish superiority with the idea of equality between Jews and Arabs; to promote social justice policies instead of the prevailing neoliberal policies; and of course, to steer Israeli society toward establishing peace with the Palestinian people and the wider region surrounding this land, instead of continuing occupation, horrors such as October 7, and the destructive war and displacement that followed.

Some may argue, out of despair, that these goals are unattainable. The answer is that indeed the task is difficult and the road is long, but we have no choice but to walk it. For this effort to have a chance, we must act among the entire public, Arab and Jewish alike, while taking into account the sensitivities, fears, and hopes of both peoples. We must ask ourselves: what is the alternative on the day Israeli society awakens from the Kahanist nightmare? Who will set the direction? Will it once again be Benny Gantz, Yair Lapid, and those who follow in their path? This is the place and this is the time when we must be present and active.

The criticisms of the ad calling for a Jewish–Arab party fall into several types. One argument — entirely legitimate — is that such a party already exists: Hadash is a Jewish–Arab party and list. Indeed, thanks to its dominant component, the Communist Party, Hadash has an internationalist ideology and includes both Arabs and Jews in its list. However, in practice, Hadash has given up on recruiting the masses in the Jewish street; its discourse is directed mainly at the Arab public, and at times lacks the sensitivity toward the Jewish public that would enable broad outreach.

Another type of criticism, heard in this forum as well, claims that as long as we live in a reality of apartheid and genocide, a Jewish–Arab party merely reproduces the existing power relations. According to this view, what is required is acceptance of Palestinian leadership within the existing parties, alongside a “temporary” Jewish relinquishment of leadership.

But the question arises: who will work to change the current reality? Can we rely on Trump or on “the world” to do so? It seems that the question of who will change reality concerns the supporters of this approach less, and since they do not engage with it, they effectively contribute to perpetuating the existing reality.

We argue that joint Arab–Jewish leadership is itself a challenge to the existing order that we seek to shake and change. In this context, it is worth asking: why is Jewish–Arab partnership in leadership considered essential in civil society organizations such as Sikkuy, Hand in Hand, Abraham Initiatives, and others, while it is deemed unacceptable in a Jewish–Arab party?

Finally, many criticisms expressed anger at the intention to “waste votes” and undermine efforts to bring down Netanyahu’s government. This concern is understandable, especially after the November 2022 elections, when Meretz and Balad lacked a few thousand votes to pass the electoral threshold — which prevented eight Knesset members from entering, potentially changing the entire political picture.

Nevertheless, although the party we called for has not yet been established, its initiators — Ghadir Hani and Maoz Inon — published a statement welcoming the agreement to re-establish the Joint List, with the aim of strengthening efforts to replace Netanyahu’s government and the Kahanist current. “For us, it is completely clear that we must act responsibly and not take steps that could endanger this outcome,” they wrote, hinting that they would not run for the Knesset if the Joint List is indeed formed. Creating a shared political home for Jews and Arabs, for Jewish women and Arab women, is a long-term mission — not a short sprint.

.png)